Deprecated: array_key_exists(): Using array_key_exists() on objects is deprecated. Use isset() or property_exists() instead in /nas/content/live/trees4future/wp-content/plugins/ht-knowledge-base/php/ht-knowledge-base-category-ordering.php on line 58

Deprecated: array_key_exists(): Using array_key_exists() on objects is deprecated. Use isset() or property_exists() instead in /nas/content/live/trees4future/wp-content/plugins/ht-knowledge-base/php/ht-knowledge-base-category-ordering.php on line 60

Deprecated: array_key_exists(): Using array_key_exists() on objects is deprecated. Use isset() or property_exists() instead in /nas/content/live/trees4future/wp-content/plugins/ht-knowledge-base/php/ht-knowledge-base-category-ordering.php on line 58

Deprecated: array_key_exists(): Using array_key_exists() on objects is deprecated. Use isset() or property_exists() instead in /nas/content/live/trees4future/wp-content/plugins/ht-knowledge-base/php/ht-knowledge-base-category-ordering.php on line 60

Section 2: Core Skills

Laura J. Spencer (1989) in her book Winning Through Participation says — “The facilitator functions much like the conductor of a symphony, orchestrating and bringing forth the talents and contributions of others.” It’s an apt analogy. In the the symphony everything from the composition to the actual notes created by the musicians do not belong to the conductor. To some the conductor is simply holding the group together as the artists deliver their performances, and yet it takes immense skill and practice to do this successfully.

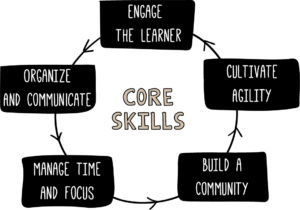

This section covers core skills a facilitator needs to master in order to support both learning and action for their group participants. The skills included here are interconnected and complement one another in helping the facilitator perform the five functions under which they are organized:

Laura J. Spencer (1989) in her book Winning Through Participation says — “The facilitator functions much like the conductor of a symphony, orchestrating and bringing forth the talents and contributions of others.” It’s an apt analogy. In the the symphony everything from the composition to the actual notes created by the musicians do not belong to the conductor. To some the conductor is simply holding the group together as the artists deliver their performances, and yet it takes immense skill and practice to do this successfully.

This section covers core skills a facilitator needs to master in order to support both learning and action for their group participants. The skills included here are interconnected and complement one another in helping the facilitator perform the five functions under which they are organized:

| Engage the Learner | Organize and Communicate | Manage Time and Focus | Build a Community (of Practice) | Cultivate Agility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l. Model Emotional Intelligence | 6.Communicate clearly | 9. Clarify goals, expectations, and agendas | 12. Create ground rules | 16. Model seeking and providing feedback |

| 2. Create a safe, inclusive space | 7. Plan and Prepare | 10. Focus the conversation | 13. Build relationships | 17. Assess and adapt |

| 3. Practice active listening | 8. Present Effectively | 11. Manage time | 14. Enable group problem solving | |

| 4. Ask effective questions | 15. Resolve conflict | |||

| 5. Facilitate whole-body learning |

Engage the Learner

Model Emotional Intelligence

The facilitator sets the tone for how members interact with one another, and serves as a role model to make the program a respectful, affirmative, rewarding experience for the participants. While many of the skills in this chapter focus on these outcomes, the following behaviors can have a tangible impact:- Being Calm: not bringing strong emotions, moods, or personal pressures to your role as a facilitator; not reacting to strong emotions within the training.

- Staying Emotionally positive: openly acknowledging negative emotions as they arise, and providing structure and positive framing that help the group tackle these constructively.

- Being intentional about your own opinions: being aware of your opinions and agendas so you are intentional and transparent in when and how you chose to influence the group. When using the Mentor and Catalyst style the facilitator stays neutral, encouraging the group to drive the agenda and thinking.

- Reflection: after each training ask yourself – how did it go? What were the emotional highs and lows? What triggered these emotions? Where did I help participants be creative and find an answer? Where did I get in the way of learning? What can I do differently?

- Feedback: seek and welcome feedback

- Alternate perspective: when you find yourself dealing with opposition, take a moment to be curious – what about the other person’s experiences and goals led them to a different conclusion?

- In-the-moment checks: pay attention to your breathing, energy levels, and emotions during a session. If you find yourself getting upset or angry, don’t hesitate to take a 5 minute break to find your calm. Once you figure out what is causing your emotions, ask yourself – is my reaction relevant to the group’s learning and progress? If not, let it go. If it can help the group get to a new insight, share it with them — but only in the context of their goals.

Create a safe, inclusive space

People learn by doing, asking questions, sharing what they know with others to generate new ideas, and participating actively in the group dialogue. To enable this the facilitator needs to create a safe space where participants can openly speak up and engage without judgement or fear of failure. You can do this by:- Better understanding the diversity of experiences represented in your farmer group.

- Using participative techniques to ensure everyone in the group gets a chance to engage and contribute.

Women account for 40% of the global agriculture labour force (50% in Eastern Africa), and make up two-thirds of the world’s poor livestock keepers. They are often responsible for critical, and under-valued activities like providing food and nutrition to the family, and procuring fuel and water (SOFA Team and Doss, C., « The Role of Women in Agriculture« , 2011, p. 1).

Melanne Verveer, Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women’s Issues for The Food and Agriculture Organization, made the following remarks highlighting the integral link between providing greater resources and support to women farmers and reducing malnutrition and poverty:

Women account for 40% of the global agriculture labour force (50% in Eastern Africa), and make up two-thirds of the world’s poor livestock keepers. They are often responsible for critical, and under-valued activities like providing food and nutrition to the family, and procuring fuel and water (SOFA Team and Doss, C., « The Role of Women in Agriculture« , 2011, p. 1).

Melanne Verveer, Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women’s Issues for The Food and Agriculture Organization, made the following remarks highlighting the integral link between providing greater resources and support to women farmers and reducing malnutrition and poverty:

“…closing the gender gap and providing women with the same resources as men could increase their individual yields by 20-30% that would in turn improve agricultural production in the developing world between 2 ½ and 4% and reduce the number of undernourished people by 100-150 million globally…Gender equality is smart economics.”

TREES is committed to supporting women farmers, and considers it a core principle of the Forest Garden program. When finalizing both timing and venue of the Forest Garden sessions take into account the daily routines and responsibilities of the women in the group. Encourage participation by ensuring that the sessions are conveniently timed and located for them. Experience and Expectations Occasionally you will have a group or a session where some members of the group are more advanced in both their skills and their expectations of the content that will be covered. The facilitator can use this to their advantage. Once you get a better understanding of the strengths and skills each farmer brings to the group — you can limit your own role and rely on them to share their knowledge with their peers through techniques like Learn-and-Teach, one-on-one mentoring connections, and having them lead small group discussions on relevant topics. When leveraging farmer expertise make sure:- You don’t rely on the same few farmers. Take time to learn more about all the members in your group to identify what others could learn from their experience.

- Find ways to draw ideas from the less knowledgeable members, who may have a fresh perspective on the issue at hand.

- Ask a question and let members raise hands and volunteer answers: this method favors extroverts and the more dominant voices the most. If used sparingly, this method can work when you have limited time. It can also be used with more mature groups where norms for equal participation are well established.

- Call upon members to answer questions: in this method the facilitator calls upon specific members to respond to a question. This method can be used strategically by the facilitator to draw out experiences and insights relevant to the topic. It is less effective at getting everyone to participate since it’s likely to make the more introverted members feel uncomfortable.

- Small-group debriefs: use small-groups for activities (below) and then bring the groups together to share insights with others. The more reserved and hesitant participants will often feel safer speaking up in smaller groups and can rely on a member who is comfortable in the spotlight to report back to the large-group.

- For a group with a handful of introverts or fewer women who may be hesitant to participate – create dedicated small-groups for these members.

- For a group where introverts or women are well represented, make sure the small-groups are diverse and represent the overall breadth of experiences that members have to offer.

- Use questions to draw out, acknowledge, and validate differences.

- Repeat key insights for the broader group.

- Highlight challenges, goals, aspirations, and characteristics that are common across members. If the group members can see what unites them, they will be more likely to learn from what makes them different.

- Ask participants to take 2-5 minutes of quiet time to think about their ideas before brainstorming for solutions or providing answers to questions.

- For small-group activities you can ask members to take a few minutes to draft their own plan, follow that with collaboration and discussion, and finally take some time at the end to amend their original plan with the ideas they gleaned from the group.

- Instead of thinking of silence as an empty space that needs to be filled, help the group consider it quiet time to get their thoughts organized.

Practice Active Listening

The primary purpose of listening is to understand the other person’s point-of-view, how they think, and what their vision on the subject is. You are listening for what inspires them, concerns them, excites them, frees them up, and keeps them from giving-up. Equally importantly, you are listening for what the individual is not saying, how they are saying it, what feelings and emotions are expressed or withheld, and what questions or topics are avoided. Listen Deeply- Listen to what is being said, but also the tone, pace, voice, and body language with which it is said.

- Give the participant your complete, undivided attention. Avoid distractions or interruptions. When others are talking, don’t spend time planning what you will say in response.

- Demonstrate you are listening with your verbal and nonverbal cues like nods, eye contact, posture and verbal affirmations. Your body language should indicate attentiveness in a culturally appropriate manner.

- Wait a few seconds before replying to what the individual has just said. Allow the individual to have the space to finish their thoughts and feelings. An extended silence can prompt the participants to think more about the issue and add a detail or two. Encourage members to build out their thoughts. You can do so by using phrases like, “tell me more”, “what else”, “can you elaborate.”

- Paraphrase and verify what you are hearing by repeating it back in your own words. Knowing exactly how and when to paraphrase in a conversation is a powerful skill developed over time through practice. Paraphrase whole concepts or major points in the conversation, rather than every little detail. Complex or emotional topics might require more regular paraphrasing to ensure the person feels understood.

- Validate group insights by summarizing and clarifying new ideas that are shared.

- If possible, request someone in the group to take notes (serve as a scribe) so you can free yourself up to listen, while making sure the ideas and solutions are being captured.

Ask Effective Questions

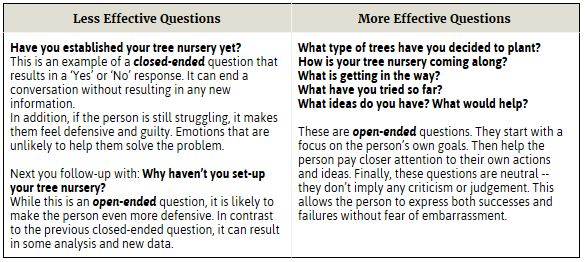

In his book, Quiet leadership: help people think better — don’t tell them what to do: six steps to transforming performance at work, David Rock (2006) quotes a Chinese fortune cookie – “Ideas are like children, there are none so wonderful as your own.” This simple fact makes questions the very heart and soul of effective facilitation. When used thoughtfully, questions can get people to think through and solve their own problems, discover their strengths, and find the resilience to take on previously unthinkable challenges. Good questions generate (1) new information, (2) raise an individual and a group’s awareness about a topic, and (3) encourage them to take accountability for action. To better understand effective questions, let’s consider an example. Perhaps a member of your farmer group has been unable to successfully establish a tree nursery. You have already told them how important it is for them to do this. In a follow-up conversation you ask them: When asking questions, keep the following in mind:

When asking questions, keep the following in mind:

- Unless you are specifically looking for a yes or no answer, open-ended questions lead to more insight and creativity.

- Questions that start with ‘what’, ‘when’, and ‘how’ tend to focus on solutions and are more effective. Unqualified ‘why’ questions that have a person focus can make people defensive and imply judgement (e.g., why have you done this?). These negative emotions can prevent individuals from coming up with new ideas. If you do need to ask ‘why’ questions, you can reframe them as ‘what are the factors-’ to evoke data driven answers.

- As a facilitator, resist the urge to ask questions that satisfy your curiosity and will help you solve the problem and offer advice. Instead, ask questions that will help the participants come up with their own ideas. To figure out which question to ask next – follow the interest and thinking being expressed by the group.

Facilitate Whole Body Learning

Consider these four things:- We have better recall and memory of facts and events that we have an emotional connection to (Tambini, Rimmele, Phelps, & Davachi, 2016).

- The human brain evolved for constant motion. In fact, our homosapien ancestors walked up to 12 miles a day. This evolutionary force has left its impression — research shows that movement improves reasoning, memory, attention spans, and planning capabilities (Medina, 2008).

- Contemporary thinking on adult learning and performance indicates that incorporating a certain playfulness in the form of movement, well designed games, and music can enhance memory and recall for participants (Visser, 1996).

- Learners walk away with more tangible skills when they actually do what we want them to learn, as opposed to hearing someone else talk about it (Prince, 2004).

- “Welcome good humor, laughter, and enjoyment of the process” (Chevalier & Buckles, 2013).

- Implement the sessions in a way that allows learners to spend the majority of their time practicing, doing, and jointly exploring a new skill.

- Keep participants moving. Design sessions so that farmers do not have to sit or stand in the same posture for longer than 10 minutes at a time.

- Pay attention to the energy levels in the group. If participants look tired or bored, take action:

- Give the group a 5 minute break.

- Sometimes a break is not feasible, and can be disruptive when learning a sequential activity that builds on the previous step. In this scenario you can introduce a change of pace by asking participants to move in response to questions. Here’s an example – “everyone who thinks the soil in their fields in loamy come stand over here”.

- Ask the group how they are doing on their energy levels and what they need in the moment to get themselves re-energized — and then honor their response. Sometimes simply asking the question can get the group re-oriented.

- Incorporate culturally appropriate songs, simple and relevant games, use of drawing or creating visuals, stories, and role-play. This can help the group look at an issue from a different perspective. This also creates some distance from the reality of the challenge, and can keep the group creative by reducing the fear of failure.

- Finally, the Forest Garden modules are designed to be conducted primarily in the field. Give some thought to the comfort of the participants. For example, if the session will span 3-4 hours, plan for breaks, a place to rest in shade, where and how group dialogue will happen, food, and refreshments.

Organize and Communicate

Communicate Clearly

Extension agents and other agricultural trainers need to know how to help farmers understand new technical content. Farmers are often illiterate or have a lower average education level than the researchers, extension agents, and other specialists who attempt to help them. It is critical not to confuse this with thinking that farmers are dumb. A good facilitator brings genuine respect for the wisdom, intelligence, creativity, and experience that farmers bring. The mention of literacy levels is to emphasize that academic and scientific terms will not transfer well to farmers. Facilitators need to package content in a way that makes it easy to understand (using appropriate language). In some cultures, farmers can often be quiet and hesitant to speak up and interject their opinion or experience. They may nod their heads or agree though verbal and nonverbal gestures despite lack of agreement or understanding. To engage farmers in dialogue that reinforces and demonstrates that learning is occurring.- Ask lots of questions to draw out knowledge (more on asking effective questions here).

- Ask lots of questions to confirm understanding.

- Give clear instructions (more details below).

- Simplify complicated topics and use simple terms.

- Speak clearly and loudly.

- If you don’t know the answer to a question, say so and commit to helping find the answer.

- Repeat questions asked by the audience so everyone can hear the question.

- Summarize long explanations provided by farmers.

- Summarize long discussions before continuing to the next topic.

Plan and Prepare

Before each module:- Review the relevant agroforestry content from the Technical Guide.

- Acquire and prepare relevant materials (samples, flipcharts, handouts, instructions, farming equipment, supplies, seedlings etc.).

- Identify a suitable location to conduct the session.

- If you will be relying on others, to role-play a story or lead parts of the session, try and connect with these volunteers ahead of time. This could be as simple as asking them to come to the session 10-15 minutes before the others, so you can share the necessary information and they can get their questions answered.

- Use your knowledge of the group — their level of confidence, skills, areas of uncertainty, and challenges — to anticipate which parts of the session might be hard for them to work through. Think of questions, tools, and activities that could make this less stressful, and boost participation and learning in these areas.

- Write clearly.

- When writing on the flipchart, try not to turn completely and face your back to the audience.

- Paraphrase by using single words and short phrases on the flip chart. Do not write out complete sentences.

- Ask someone else to serve as the scribe while you listen and engage the group. This minimizes the starting and stopping that happens when the same person facilitates and writes.

- When finishing a flip chart page, hang the flip chart elsewhere and keep it visible rather than turning it over to the backside of the flipchart.

- When using flipcharts in the field, find a lightweight but sturdy item such as a cardboard box or piece of plywood to serve as a backdrop for the flipchart.

Present effectively

As mentioned earlier, where you need to take on the role of a trainer and educator, make sure you keep your presentation no longer than 15-20 minutes. It is hard to hold an audience’s interest for much longer than that. And you will find that creating a simple, short talk often takes more work and effort than one that rambles on for an hour. 1. Practice. Prepare your content ahead of time. It can be helpful to write down key points and rehearse what you will be saying. The idea is not to memorize the content – instead practice the overall flow and sequence. 2. Organize the content. Our brain acquires knowledge by turning new information into a mental map and connecting it to the things we already know (Rock, 2006). Make it easier for participants to learn by doing this for them. Identify the main ideas. Organize them in a logical sequence where each idea builds on the other. When you start, take a minute to walk them through a high level outline of what you will be talking about. Ideally have it written down on a flipchart so they can follow along. Here is an example: “Let us spend 10 minutes to learn how to pretreat seeds. We will talk about:Why we should pretreat seeds? Which seeds should be pretreated? Which method to use?”

Next provide more information for each of the key points in the outline. Use questions and discussions to validate and solidify learning. 3. Simplify. We reiterate this point throughout the introduction – use simple language, and avoid jargon. Use metaphors, examples, and stories to convey more complex ideas. 4. Make it a conversation. When delivering your content do not read from a script or deliver it like a speech. Keep it conversational and natural, as if you were explaining it to a friend. Even when you are presenting new technical information and techniques, you can intersperse it with questions to involve the group throughout your talk. Frame each point as a question to get the farmers to think about their own answers, so they can connect what you are sharing with what they already know. 5. Deliver with a calm posture. This is perhaps the hardest part of presenting to others. For those of us who are nervous, while we can master our voices, our bodies and shaky hands can sometimes undermine our confidence. All the preceding points — preparation, making it a conversation, using questions and participation — will help you overcome this. If our goal is to impress others, we will likely be nervous. If our goal is simply to help them the best we can, we will be less worried about being perfect and our bodies will feel calmer. Here are a few additional tips:- Use deep, slow breaths and a tall posture to calm yourself.

- Stay away from excessive fidgeting and movement. These can be distracting to your audience.

- Sometimes holding a piece of paper, or standing next to a flipchart can help you use your hands more effectively as you talk.

Manage Time and Focus

At any given time a facilitator is trying to balance two things: (1) helping participants have meaningful conversations that further their learning; and (2) manage the agenda and the time so that participants can meet their overall learning goals. It can take practice, and a degree of trial-and-error to master the art of getting groups to have deep dialogues, and then asking them to switch contexts and move on to the next topic at hand. The skills included under this theme provide pointers on how to manage this tension.

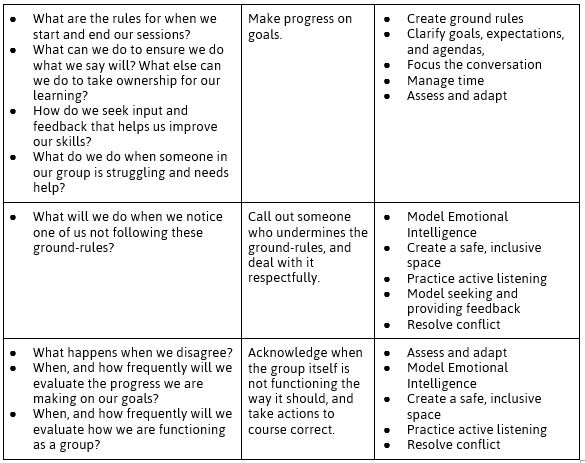

Clarify goals, expectations and agendas

Create clarity on goals A goal is defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “the end towards which effort is directed.” Goals within the context of the Forest Garden program can exist at many levels. At the highest level, your goal as the facilitator is to help farmers create thriving Forest Gardens of their own in the four year period, and to help them build skills and a supportive community that can sustain these. Farmers may not see this overall goal in the same terms. For them it may be more specific and personal: not having to work as a migrant laborer during dry months, being able to feed their families, sending their children to school, building a home, finally starting that business they have dreamed about. In Module 1 you help farmers create a clear picture of what their own Forest Garden will look like through the Dream Field exercise. You should also help them define what this Forest Garden will free them up to do in their lives. Similarly, each module has a clear goal for the facilitator (e.g., set-up tree nurseries, plant agroforestry trees). Use questions early on in each session to help farmers identify the personal relevance of these objectives. When you help farmers be more aware and clear about their individual goals – they will be more motivated to take accountability for making progress. Get to common expectations Expectations are what the farmers think will happen in the program overall, and in specific sessions, prior to it starting. We commonly, and mistakenly, assume that others have the same expectations of an event as we do. Given how varied each individual’s attitudes, needs, and past experiences tend to be — it is best not to make this assumption. Begin each session by clarifying expectations. This has two advantages:- The obvious benefit of helping all participants come to a common understanding of what will happen in each session.

- It focuses participant attention on the work at hand, and helps them step away from the concerns and tasks that may have been occupying their mind as they came to the workshop.

Focus the conversation

Getting group members to share personal experiences and generate a broad range of ideas is a hallmark of an effective facilitator — as long as you can help the group identify key learnings from this rich dialogue, and ensure that the conversation moves forward. You can do this by:- Identifying and separating key points and themes. Example, “I am hearing these three themes emerging from what all of you shared…did I hear this right? Did I miss anything?”

- Zooming to the right level of detail. Using a metaphor from photography, if you hear a participant get lost in the details help them zoom-out. You can ask questions like — what is the key take-away; what is the most important lesson you learned. On the other hand, if someone’s observation is too general help them zoom-in by asking for examples and situations that will add more detail.

- Sequence questions and topics. As new topic threads and questions emerge, clearly identify the order in which the group will work through them.

Manage time

Next to self-awareness, this is perhaps the toughest skill of all and here is why — interrupting participants and cutting-off dialogue in a way that does not appear rude is hard; plus it takes practice to know when it’s time to move on to the next topic. Here are some techniques and principles to help you get started:- Use the parking lot. When participants have a discussion that goes on to topics that were not planned, you can decide to bring the discussion back to the original agenda. If the new topic is important, you can place it in the parking lot. The parking lot is a widely used technique which entails using a flipchart to write down topics that will be revisited after priority content is covered.

- Get to good-enough. Farmers don’t need to fully resolve a topic during a session for learning to happen. In fact, more often than not, the discussion serves as a starting point. It sparks ideas and provides new knowledge that members must experiment with on their fields to fully learn and acquire a new skill. Knowing this, when key points have been covered, find a respectful opening to transition to the next topic.

- Know when to go off-track. Sometimes, the conversation that evolves is more important than the originally planned topic. If farmers are more interested in discussing a pressing challenge than covering content previously planned by the facilitator, then the change in topic may be necessary. To determine when to do so ask yourself – what will best further learning and Forest Garden goal achievement for the participants?

- Create a nonverbal cue to get small-groups to close their conversation. While small group activities are great for learning and participation, new facilitators can struggle with bringing small group discussions to a close in a timely manner. They typically end up raising their voices to be heard above the conversational din, and despite that it can take a while to be heard. To avoid this, set a consistent nonverbal cue ahead of time. For example you could say – ‘When you see me walking around with my arm raised above my head, please bring your conversations to a close and turn your attention to the larger group.’

Build a community

For a group to work together and function effectively, it must have the ability to get things done (focus on tasks) and have strong trusting relationships that can weather the conflict and friction that is inevitable when collaborating (focus on relationships). By helping the group integrate and self-manage tasks and relationships, the facilitator can serve as a catalyst that transforms them from a group of disparate individuals into a community that supports and strengthens its members. The belief that together the participants can be more effective, and generate outputs that far outpace what they would accomplish alone, holds this community together. In the case of farmers this is especially true. When farmers work together they can pool resources, lower input costs for labour and equipment, and leverage collective bargaining to get more money for their produce.

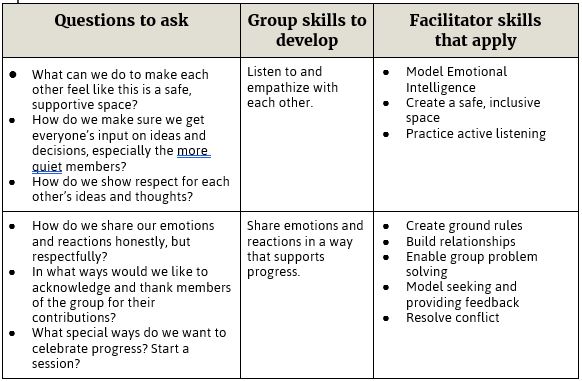

Create ground rules

Ground rules influence and support norms that govern the time participants spend together. The open and collaborative nature of establishing ground rules sets the tone that the farmers own the workshop, not the facilitator. In their very first session together, participants decide what the rules should be. Where there is disagreement, the facilitator uses participative techniques to help the group reach consensus. Finally, the group determines the consequences of not following the ground rules, and takes collective accountability for upholding and enforcing these. Here are some questions the facilitator can ask to help the group create the ground-rules: Ground rules help the community take-on tasks that the facilitator would typically perform for them. When members own and evolve the process by which they work together, they develop their group maturity. In their article, Building the Emotional Intelligence of Groups, Vanessa Druskat and Steven Wolff make the following observation:“Group emotional intelligence is about the small acts that make a big difference. It is not about a team member working all night to meet a deadline; it is about saying thank you for doing so. It is not about in-depth discussion of ideas; it is about asking a quiet member for his thoughts. It is not about harmony, lack of tension, and all members liking each other; it is about acknowledging when harmony is false, tension is unexpressed, and treating others with respect” (Druskat & Wolff, 2001).

To that effect, creating ground rules is not a one-time activity. The facilitator should post these up on a flipchart at every session, and encourage the group to actively reflect on and adapt them as needed.Build relationships

Trusting relationships are the cornerstone of an effective community. Think of someone in your own life that you trust. Its likely this person:- Cares deeply about your well-being, and remembers what is important to you.

- Provides help and support to you, both through their words and their gestures.

- Follows through on commitments they have made to you.

- Is honest and tells you when they observe you doing something that may not be in your best interest.

- Allows you to reciprocate the help and support by sharing their own challenges and emotions with you.

Enable group problem solving

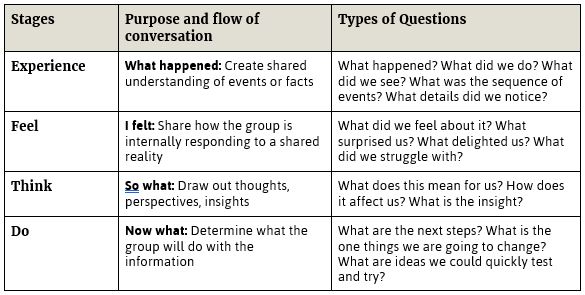

You can use a method called Structured Dialogue to help the group solve problems, assess progress, and start the process of generating ideas and solutions. It involves you asking a series of questions that are designed to bring structure and focus to group conversation, and free people up to be creative, honest, and respectful. This framework is inspired by methods used in Design Thinking, coaching and feedback techniques, and the Focused Conversation method developed by the Institute of Cultural Affairs (ICA) in Canada as part of their Technology of Participation (ToP®) facilitation method. The method can help groups unpack their experience, identify shared insights, and generate ideas and solutions they can quickly test to tackle tenacious challenges. Understanding the framework The Structured Dialogue framework consists of four stages:- Clarify the experience or what happened. This could be an event, a challenge and how it has unfolded so far, a task or activity individuals in the group are working on. The events should be described in neutral terms, without judgement or editorial comments – as if members were narrating something a video camera captured.

- Share the emotions the experience has evoked. People should be challenged to express their emotions in a way that allows others to get an honest insight into how they feel, without making anyone else feel attacked or accused of causing these emotions. Using ‘I’ statements that are focused on the experience rather than a person helps do this. For example “I felt unhappy when we started late” versus “You made me unhappy when you arrived late”.

- Describe the impact of the experience. Help members share what it means for them. This is where the group can start to identify implications, relevance, importance, and consequences.

- Ask what can be done differently. The focus is on generating ideas for real action that can be taken either collectively or by each individual. The group should be encouraged to be creative, and think out-of-the-box at this stage. In addition, help them think of small steps they can take to quickly test if an idea will work.

When applying the framework, make sure:

When applying the framework, make sure:

- Everyone gets a chance to contribute and participate, and that the dialogue is not dominated by the voices of a few. The ‘Create a safe, inclusive space’ skill covered in Section II: Core Skills, ‘Engage the Learner’ chapter (pg x) provides more guidance on how to do so.

- Do justice to each stage in the conversation. There is a tendency to skip or rush through the Experience and Feel stages, especially for groups that are not accustomed to sharing or talking about their feelings.

- At the same time, be mindful of the overall time available for the activity and keep the conversation moving. Be tenacious about helping the group identify insights and actions coming out of the dialogue.

Resolve conflict

Groups can experience three types of conflict (Jehn, 1997):- Task Conflict: this conflict is focused on outcomes the group generates, including decisions and approaches on how to do this. Task conflict can be generative. In a group that encourages and accepts voicing of different opinions it can improve group performance by helping members evaluate and integrate different ideas and ways of implementing them.

- Process Conflict: this is focused on how the group functions, who takes responsibility for what, how decisions are made, and roles played by various members — in short the group norms. High process conflict can create lack of clarity and impedes group performance.

- Relationship Conflict: relates to personality dynamics, member attitudes towards one another, and interpersonal conflict. It is the hardest of the three to resolve, and negatively impacts the group’s ability to make progress and get things done. When task and relationship conflict go unresolved and are allowed to fester, they can evolve into relationship conflict.

- Supportive norms: Groups that create and maintain norms that support inclusiveness, mutual respect, and encourage members to raise concerns and share emotions constructively (see Create ground rules, page xx) are better positioned to deal with conflict and tension.

- Healthy emotional expression: How the group deals with and expresses emotions is key. Negative emotions are like steam — they will escape one way or the other. When suppressed these emotions are likely to cause inadvertent and hurtful outbursts. But if they are expressed intentionally, honestly, and constructively they can generate powerful forward momentum.

- Positive framing: The facilitator can nip conflicts in the bud by restating negative statements positively, and helping others do the same. For example, when someone says ‘You go on and on about things that are not relevant’, you could restate that to ‘If I understand correctly, you will learn better from your peer when they are direct in pointing out the tip they want to share.’

- Curiosity plus the power of ‘and’: In the same vein, when members build on each other’s ideas, ask them to start their statements with ‘and’ instead of ‘but’ even if they feel like they are contradicting the previous statement. Help members see that two, supposedly opposite things, can be true at the same time. These differences in opinions, stemming from our experiences, can contain data and learning when we approach them with curiosity. For example, if two farmers are reporting dramatically different vegetable sales prices in the same month — instead of assuming one of them is wrong — the group can ask questions to learn from this disagreement (What do we consider a high or low price? What market are you selling in? What’s the difference in our buyers and quality of crops?)

- Gratitude: shifting focus to the positive contributions of our peers can be an effective antidote to task related tensions. If the group is experiencing friction, conduct an acknowledgement exercise where you go around the room and ask each person to share something they enjoy and love about the group. This will build positive energy to counter and ease the conflict.

- Structure shifts focus to shared challenge: using a conversational framework (e.g., Structured Dialogue, or Feedback Statements) can depersonalize the conflict. It helps participants freely voice ideas and feelings with a focus on the problem at hand, rather than focusing on each other.

Cultivate Agility

The agroforestry skills farmers learn in each module helps them design and create their very own Forest Garden. The skills you embody and cultivate when you help them grow as a community (previous chapter) and adapt to the realities on-the-ground (this chapter) allow them to sustain their Forest Garden through the inevitable setbacks they are likely to face.Model seeking and providing feedback

To create a culture where the participants are open to new ideas and willing to take input — you as the change-agent in the group should seek frequent feedback on what you are doing. When you do this, you serve as a powerful role-model letting the group know that it is ok to ask others for ideas and help on how to do something better. Bernard Roth, in his book The achievement habit: stop wishing, start doing, and take command of your life, describes two simple statements designed to generate feedback that encourages learners to improve their ideas and solutions, and builds their confidence instead of making them feel criticized and judged (Roth, 2015). It involves:- Two ‘I like’ statements. Example: I like the pattern in which you have planted the vegetables. I also like the choice of vegetables that balance soil givers and takers.

- Followed by one ‘I wish’ statement. Example: I wish there was a way to better protect the vegetable nursery from pests.